Inquiries Of Our Reality - Introduction to the Cynocephali

In this podcast, the discussion centers around the concept of the Cynocephali, or "dog-headed people," as described by various historical figures, including Herodotus, Vincent of Beauvais, Isidore of Seville, Ctesias, and Marco Polo.

Below are the podcast notes from my latest episode on Inquiries Of Our Reality. In this podcast, the discussion centers around the concept of the Cynocephali, or "dog-headed people," as described by various historical figures, including Herodotus, Vincent of Beauvais, Isidore of Seville, Ctesias, and Marco Polo.

Herodotus, in his Histories, mentions the Cynocephali among other fantastical creatures, assuming readers are familiar with them. Vincent of Beauvais, in his Speculum Maius, elaborates on the Cynocephali, describing them as monstrous beings from India with dog heads that bark rather than speak. Isidore of Seville, six hundred years prior to Vincent, echoes this description in his Etymologies, categorizing them as one of the monstrous races of humanity.

Ctesias, a Greek historian, provides a more detailed account of the Cynocephali in his work summarized by Photius. He describes them as living in the mountains, communicating through barking, and leading a primitive lifestyle. Ctesias claims to have witnessed some of their customs and emphasizes their unique characteristics, such as their longevity and hunting skills.

The podcast also touches on the Hieroglyphics of Horapollo, which associates the Cynocephalus with various symbolic meanings in ancient Egyptian culture, including its representation of the moon and its connection to writing and priesthood.

Marco Polo's accounts further illustrate the existence of dog-headed people in his travels, describing them as cruel and savage inhabitants of the island of Angamanain.

Interestingly, while many historical accounts affirm the existence of the Cynocephali, they often dismiss the notion of werewolves, suggesting a distinction between mythical creatures and the common acknowledgement of a real race of dog-headed people.

Herodotus

Herodotus: The Histories. Book 4, Melpomene. 191

"In that country are the huge snakes and the lions, and the elephants and bears and asps, the horned asses, the dog-headed and the headless men that have their eyes in their chests, as the Libyans say, and the wild men and women, besides many other creatures not fabulous."

Herodotus assumes the reader understands what a Cynocephali is. Let’s look at some definitions from Medieval encyclopedias.

Encyclopedias

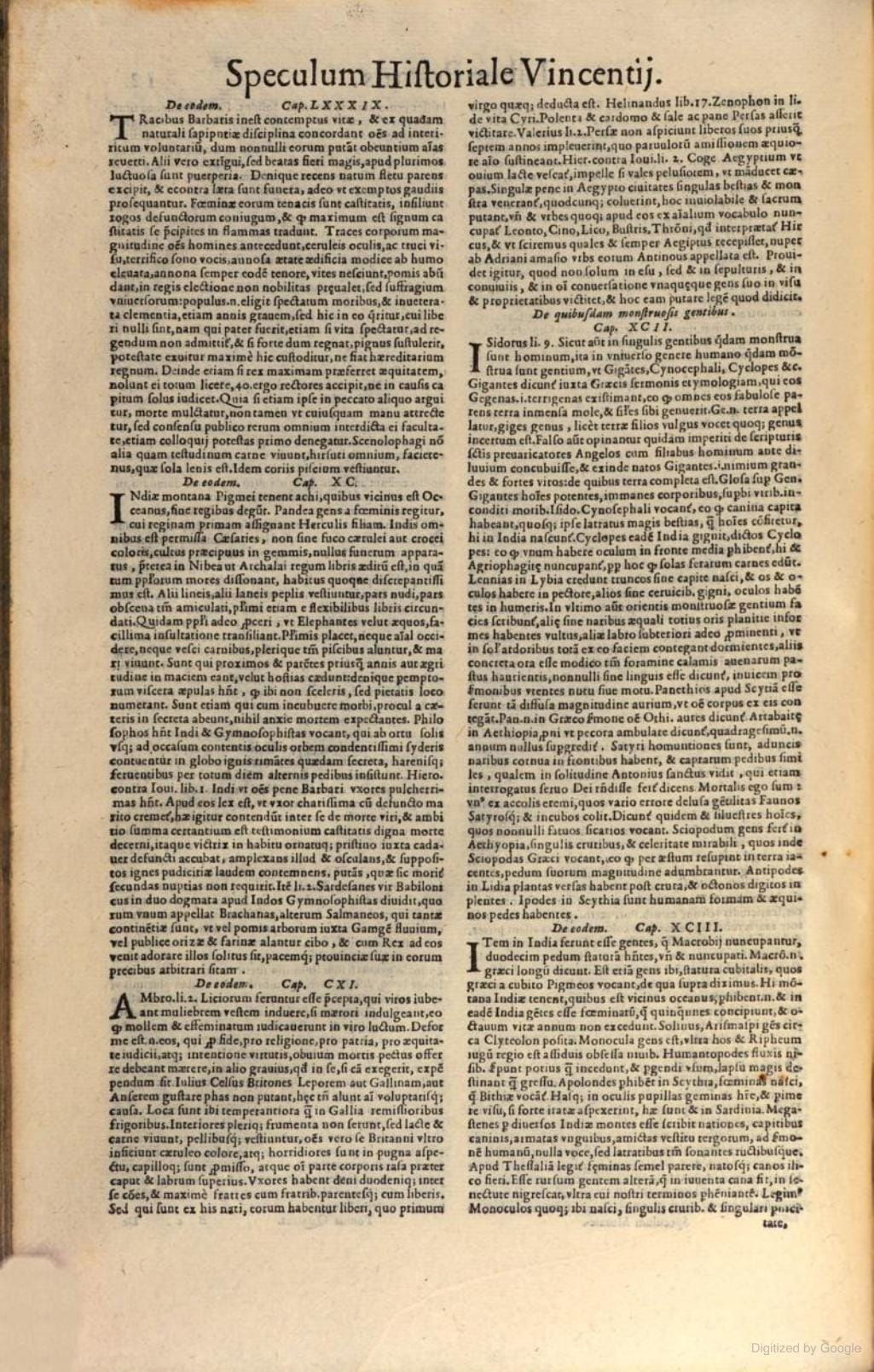

Vincent of Beauvais was a French Dominican friar and encyclopedist who lived from c. 1184/1194 to c. 1264. He is best known for his Speculum Maius, a massive encyclopedia that was one of the most important works of scholarship in the Middle Ages. Vincent of Beauvais was a prolific writer and a brilliant thinker. His work had a profound impact on the development of scholarship and education in the Middle Ages. He is considered one of the most important figures in the history of the Dominican order. The Speculum Naturale is the first part of Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Maius, and in it, he speaks of the cynocephali as originating in India (much like many previous historians).

Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum Maius

"Just as there are some monstrous humans in individual peoples, so too are there monstrous peoples in the entire human race, such as Giants, Cynocephali (Dog-Heads). . . Cynocephali are called so because they have dog heads, whose barking identifies them more as beasts than humans. They are born in India."

Isidore of Seville (c. 560 – April 4, 636) was a Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of the ancient world". Isidore was also a skilled diplomat, and he helped to negotiate peace between the Visigoths and the Byzantine Empire. He was known as a wise and educated man, being respected by both Christians and Muslims alike.

Isidore's most famous work is The Etymologies, a vast encyclopedia of knowledge that is divided into 20 books. The Etymologies covers a wide range of topics, including grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, theology, and natural science. It was a popular work in the Middle Ages, and it was used by scholars and students for centuries.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 11.3.12–14

"Just as, in individual nations, there are instances of monstrous people, so in the whole of humankind there are certain monstrous races, like the Giants, the Cynocephali (i.e. ‘dog-headed people’), the Cyclopes, and others...The Cynocephali are so called because they have dogs’ heads, and their barking indeed reveals that they are rather beasts than humans. These originate in India."

Ctesias According to Photius

The only reason we still have the writings of Ctesias is because Photius wrote both summaries and quotations of his works for his friend Tarasius among many, much shorter, summaries of various texts.

- Photius 72

- 9th Century AD

- The Patriarch of Constantinople

- The Myriobiblon (meaning "Ten Thousand Books")

- Written for Tarasius

- Summaries of 279 books

- Wrote about Ctesias' historic works on:

- Persia

- India

- 10,000+ words compared to avg of 400-500 words

- Ctesias

- Greek physician and historian

- Achaemenid king, Artaxerxes II

- Involved in war

- Involved in treaties and negotiations

- Economies - distribution of wealth

- Disagreed with Herodotus in many respects but agreed Cynocephali existed

Myriobiblon 72

"he differs almost entirely from Herodotus, whom he accuses of falsehood in many passages and calls an inventor of fables."

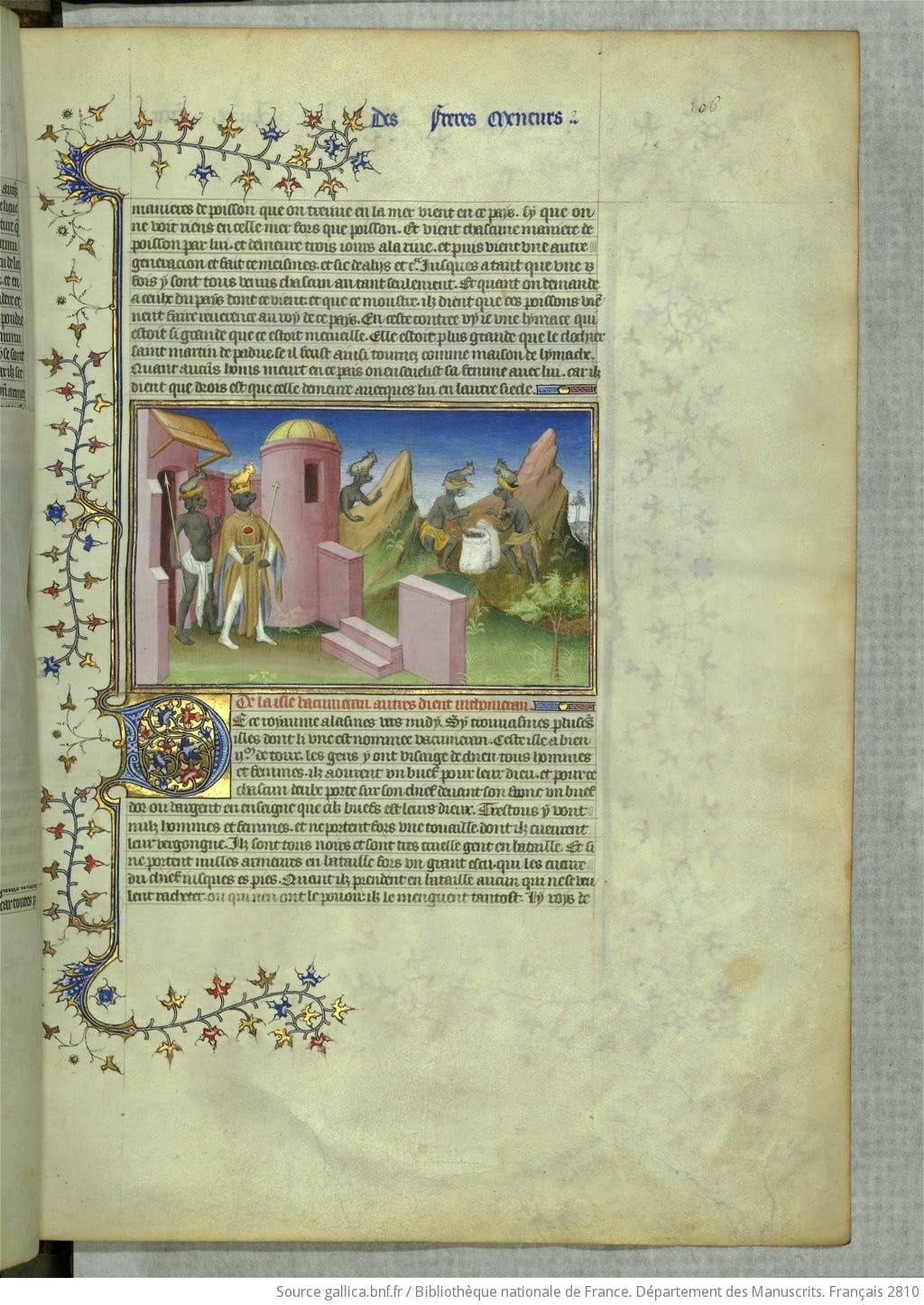

Ctesias, Indica Fragment (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 72) (trans. Freese) (Greek historian circa 4th B.C.):

"On these mountains there live men with the head of a dog, whose clothing is the skin of wild beasts. They speak no language, but bark like dogs, and in this manner make themselves understood by each other. Their teeth are larger than those of dogs, their nails like those of these animals, but longer and rounder. They inhabit the mountains as far as the river Indus. Their complexion is swarthy. They are extremely just, like the rest of the Indians with whom they associate. They understand the Indian language but are unable to converse, only barking or making signs with their hands and fingers by way of reply, like the deaf and dumb. They are called by the Indians Calystrii, in Greek Cynocephali ("dog-headed"). [They live on raw meat.] They number about 120,000.

Near the sources of this river13 grows a purple flower, from which is obtained a purple dye, as good in quality as the Greek and of an even more brilliant hue. In the same district there is an animal about the size of a beetle, red as cinnabar, with very long feet, and a body as soft as that of a worm. It breeds on the trees which produce amber, eats their fruit and kills them, as the woodlouse destroys the vines in Greece. The Indians crush these insects and use them for dyeing their robes and tunics and anything else they wish.14 The dye is superior to the Persian.

The Cynocephali living on the mountains do not practice any trade but live by hunting. When they have killed an animal they roast it in the sun. They also rear numbers of sheep, goats, and asses, drinking the milk of the sheep and whey made from it. They eat the fruit of the Siptakhora, whence amber is procured, since it is sweet. They also dry it and keep it in baskets, as the Greeks keep their dried grapes. They make rafts which they load with this fruit together with well-cleaned purple flowers and 260 talents of amber, with the same quantity of the purple dye, and 1000 additional talents of amber, which they send annually to the king of India. They exchange the rest for bread, flour, and cotton stuffs with the Indians, from whom they also buy swords for hunting wild beasts, bows, and arrows, being very skillful in drawing the bow and hurling the spear. They cannot be defeated in war, since they inhabit lofty and inaccessible mountains. Every five years the king sends them a present of 300,000 bows, as many spears, 120,000 shields, and 50,000 swords.

They do not live in houses, but in caves. They set out for the chase with bows and spears, and as they are very swift of foot, they pursue and soon overtake their quarry. The women have a bath once a month, the men do not have a bath at all, but only wash their hands. They anoint themselves three times a month with oil made from milk and wipe themselves with skins. The clothes of men and women alike are not skins with the hair on, but skins tanned and very fine. The richest wear linen clothes, but they are few in number. They have no beds, but sleep on leaves or grass. He who possesses the greatest number of sheep is considered the richest, and so in regard to their other possessions. All, both men and women, have tails above their hips, like dogs, but longer and more hairy. They are just, and live longer than any other men, 170, sometimes 200 years."

"Ctesias relates these fables as perfect truth, adding that he himself had seen with his own eyes some of the things he describes, and had been informed of the rest by eye-witnesses. He says that he has omitted many far more marvellous things, for fear that those who had not seen them might think that his account was utterly untrustworthy."

Photius wrote 10,748 words on Ctesias and his writing. That's 23 times the size of the average length of his summaries 462, making it one of the longest sections.

The Hieroglyphics Of Horapollo Niliacus

Princeton University Press

"Written reputedly by an Egyptian magus, Horapollo Niliacus, in the fourth century C.E., The Hieroglyphics of Horapollo is an anthology of nearly two hundred “hieroglyphics,” or allegorical emblems, said to have been used by the Pharaonic scribes in describing natural and moral aspects of the world. Translated into Greek in 1505, it informed much of Western iconography from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries. This work not only tells how various types of natural phenomena, emotions, virtues, philosophical concepts, and human character-types were symbolized, but also explains why, for example, the universe is represented by a serpent swallowing its tail, filial affection by a stork, education by the heavens dropping dew, and a horoscopist by a person eating an hourglass."

Hieroglyphics of Horapollo, tr. Alexander Turner Cory, 1840 AD, Originally 400 AD

"To denote the moon, or the habitable world, or letters, or a priest, or anger, or swimming, they pourtray a CYNOCEPHALUS. And they symbolise the moon by it, because the animal has a kind of sympathy with it at its conjunction with the god. For at the exact instant of the conjunction of the moon with the sun, when the moon becomes unillumined, then the male Cynocephalus neither sees, nor eats, but is bowed down to the earth with grief, as if lamenting the ravishment of the moon: and the female also, in addition to its being unable to see, and being afflicted in the same manner as the male, ex genitalibus sanguinem emittit: hence even to this day cynocephali are brought up in the temples, in order that from them may be ascertained the exact instant of the conjunction of the sun and moon. And they symbolise by it the habitable world, because they hold that there are seventy-two primitive countries of the world; and because these animals, when brought up in the temples, and attended with care, do not die like other creatures at once in the same day, but a portion of them dying daily is buried by the priests, while the rest of the body remains in its natural state, and so on till seventy-two days are completed, by which time it is all dead. They also symbolise letters by it, because there is an Egyptian race of cynocephali that is acquainted with letters; wherefore, when a cynocephalus is first brought into a temple, the priest places before him a tablet, and a reed, and ink, to ascertain whether it be of the tribe that is acquainted with letters, and whether it writes. The animal is moreover consecrated to Hermes [Thoth], the patron of all letters. And they denote by it a priest, 1 because by nature the cynocephalus does not eat fish, nor even any food that is fishy, like the priests. And it is born circumcised, which circumcision the priests also adopt. And they denote by it anger, because this animal is both exceedingly passionate and choleric beyond others:—and swimming, because other animals by swimming 1 appear dirty, but this alone swims to whatever spot it intends to reach, and is in no respect affected with dirt."

Marco Polo

Marco Polo, as you might know, was a Venetian merchant and explorer who traveled to Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in The Travels of Marco Polo, a book that describes for Europeans the wonders of China, its capital Peking (now Beijing), and other cities and countries of Asia.

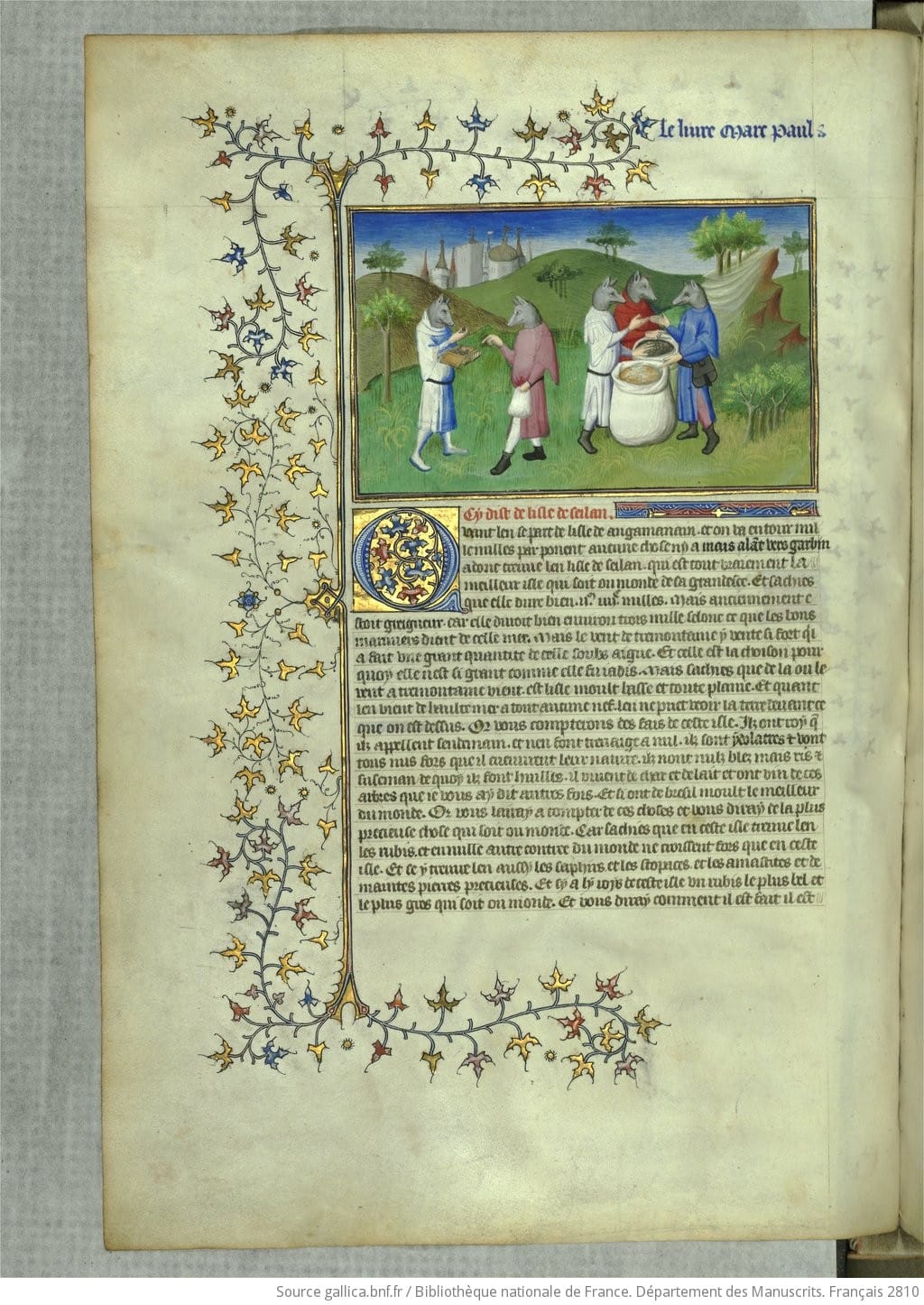

The Travels of Marco Polo: Book 3, Chapter 13

"Angamanain is a very large Island. The people are without a king and are idolaters, and no better than wild beasts. And I assure you all the men of this Island of Angamanain have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes likewise; in fact, in the face they are all like big mastiff dogs! They have a quantity of spices; but they are a most cruel generation, and eat everybody that they can catch, if not of their own race. They live on flesh and rice and milk, and have fruits different from any of ours. Now that I have told you about this race of people, as indeed it was highly proper to do in this book, I will go on to tell you about and Island called Seilan, as you shall hear."

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52000858n/f217.item

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52000858n/f160.item

Werewolves? Nope

Strangely enough, those who claimed the Cynocephali did or might exist frequently refused the notion of werewolves, deeming that concept a stretch too far.

Histories, Book 4

"These men it would seem are wizards; for it is said of them by the Scythians and by the Hellenes who are settled in the Scythian land that once in every year each of the Neuroi becomes a wolf for a few days and then returns again to his original form. For my part I do not believe them when they say this, but they say it nevertheless, and swear it moreover."

Piny The Elder, Natural History 8.34:2-4

"That men have been turned into wolves, and again restored to their original form, we must confidently look upon as untrue, unless, indeed, we are ready to believe all the tales, which, for so many ages, have been found to be fabulous. But, as the belief of it has become so firmly fixed in the minds of the common people, as to have caused the term "Versipellis" to be used as a common form of imprecation, I will here point out its origin."

City of God 18.18

"Indeed we ourselves, when in Italy, heard such things about a certain region there where landladies of inns, imbued with these wicked arts, were said to be in the habit of giving to such travellers as they chose, or could manage, something in a piece of cheese by which they were changed on the spot into beasts of burden, and carried whatever was necessary, and were restored to their own form when the work was done. Yet their mind did not become bestial, but remained rational and human, just as Apuleius, in the books he wrote with the title of The Golden Ass, has told, or feigned, that it happened to his own self that, on taking poison, he became an ass, while retaining his human mind. These things are either false, or so extraordinary as to be with good reason disbelieved. . . I cannot therefore believe that even the body, much less the mind, can really be changed into bestial forms and lineaments by any reason, art, or power of the demons;. . .These things have not come to us from persons we might deem unworthy of credit, but from informants we could not suppose to be deceiving us. Therefore what men say and have committed to writing about the Arcadians being often changed into wolves by the Arcadian gods, or demons rather, and what is told in song about Circe transforming the companions of Ulysses, if they were really done, may, in my opinion, have been done in the way I have said."